Speech

People who develop facial palsy are often concerned about their speech. Commonly reported problems are:

People who develop facial palsy are often concerned about their speech. Commonly reported problems are:

-

- Slurred speech

- Difficulty being understood by other people especially over the phone

- Fatigue when speaking for long periods

- Dribbling when speaking

- Feeling self-conscious when speaking because it emphasises facial asymmetry

- Tripping over certain words or sounds

- Loss of confidence in speaking

- Feeling that speaking sounds very different from before their facial palsy

There may be several factors contributing to these symptoms and speech may vary depending on the stage of recovery. In order to understand how facial palsy affects speech, it is helpful to know about the muscles we use for speaking.

Causes

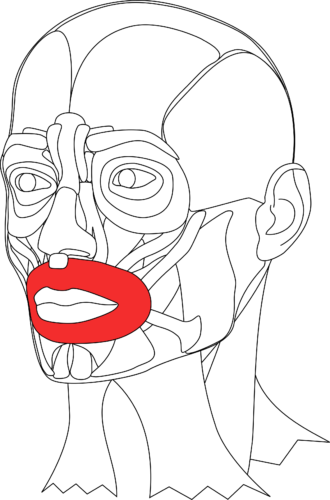

The facial nerve is not responsible for the tongue movements required for speech, for example, ‘t’, ‘d’, ‘k’, ‘g’, ‘s’, ‘z’, ‘ch’ or ‘dg’ plus all of the vowel sounds. Consequently, the majority of speech sounds remain normal and unharmed by facial palsy. However, there are two big muscles involved in speech which are operated by the facial nerve – the orbicularis oris (lip muscle) and the buccinator muscle (cheek muscle). These orbicular iris is highlighted in red and the buccinator in green in the diagrams below. The arrows show the direction of their movement.

Lip Muscle (Orbicularis Oris)

The lip muscles pull the lips inwards to the centre – they do not move the lips outwards. The lip muscles around the lips for speech sounds, for example, ‘w’, and brings the lips together for sounds, such as, ‘p’ and ‘b’. The lips have other non-speech functions, such as pucker, whistle, pressing together and rolling inwards. The lips also form a seal when we swallow. We need to swallow our saliva, so it does not build up in our mouth or trickle out. Importantly, when the lips don’t meet properly, then the person with facial palsy may experience some dribbling even when not speaking. This is not inevitable and some people may not notice any difficulty at all.

Deep Cheek Muscle (Buccinator )

Buccinator is one of the largest facial muscles and sits right on the inside of the cheek next to the teeth. It presses the cheek against the teeth and so helps keep the food central in our mouth or between our teeth for chewing. It is also responsible for keeping the air stream central in our mouths as we speak. When the buccinator muscle is weak it can no longer direct the airflow centrally as we speak. Secondly, because it is weak it has no resistance to the air pressure as it flows through the mouth during speech. As a result, the cheek tends to puff out as air escapes down the inside of the cheek. This air escaping and puffing out the cheek alters the sound of the speech.

To summarise, the main speech sounds that are affected are ‘w’, ‘p’ and ‘b’. In some people, additional sounds ‘f’ and ‘r’ may also be affected. In addition, due to weakness in the cheek and lip muscles, there may be audible air loss which both the listener and the speaker can hear. This sound may make speech less clear. Finally, there may also be some loss of saliva control and the speaker may experience some slight dribbling when talking for any length of time.

There are other muscles involved in the speech mechanism, but they tend to play a minor role and are not included in this article.

What can help

It is during the early flaccid stage of recovery when speech may be most obviously affected due to muscle weakness and loss of muscle control. Even for those who experience slow recovery, this is likely to resolve reasonably well in the majority of cases. In the interim, there are several things you can do to help minimise any obvious changes in your speech.

- If the cheek muscle is very weak and puffing out when you speak then press the palm of your hand against your cheek to stop this from happening. This is especially helpful if you are on the telephone which often distorts sounds at the best of times. In company, you might just find a pose which you can use to disguise the fact that you are supporting your cheek.

- You may find that supporting your bottom lip with your finger helps improve your speech for sounds or words which cause your problems. Adopting a pose with the thumb under the chin and the index finger curled under the bottom lip can disguise the fact that you are supporting your bottom lip.

- When your facial muscles regain some strength and shape (link to the paretic stage of recovery) you may find that it is enough just to slow down your rate of speech to improve clarity. This is because weak muscles just take longer to get to where they need to be for speech so slowing down allows them more time. It will also give you time to think if you are tripping over some words. It also gives the listener a longer time to decode what is said should there be any problems with clarity.

- Managing the ambient noise may help people understand you more easily especially if you have elderly relatives or friends who have hearing loss and may struggle to understand you more than others. Keeping the ambient noise low will enable the listener to concentrate on your speech without having to manage the surrounding sound.

- If you are worried that speaking for any length of time emphasises your facial asymmetry, then try to dampen down the unaffected side of your face. The unaffected side may have become very dominant because it wants to compensate for the weak side, and you may inadvertently be overcompensating on the unaffected side. To dampen down the overactivity on the uninjured side, place your palm against your uninjured cheek. Allow the weight of your hand to pull the cheek downwards. You could practice this when you are alone by reading a paragraph aloud from a book or magazine. Inhibit the movement a little with the palm of your hand on the affected side. You could also try and tell that side of your face not to do so much and go back to relaxing your face at rest at regular intervals.

- If you are experiencing fatigue when you speak for longer periods, then it may be better to avoid prolonged conversations or similar situations. Secondly, as above, your face may feel tired because the unaffected side is overworking so try and dampen down the overactivity and try some facial relaxation while others are speaking. Too much effort creates muscle tension and tightness so again slowing down and taking your time may help prevent fatigue.

- If your affected facial muscles have become shortened and tight you may find that the buccinator muscle is acting as an anchor on your lip muscle, preventing it from moving even though it can.

Dribbling

This is most often noticed during the flaccid stage of recovery and for most people, it will recover spontaneously. One tip is to swallow more often and have some water to hand to sip regularly if you are speaking for any length of time. Try not to keep dabbing the corner of your mouth with a tissue. This is for several reasons, firstly, because it draws attention to your mouth and the listener may have been unaware of any problems you may be experiencing. Secondly, you will make the corner of your mouth sore which just adds to the problem. Thirdly, it may be that you are just worried about dribbling and have become self-conscious. Ask a trusted friend or family member to give you some feedback and perhaps you will find that things are not as obvious as you may think.

Confidence

Some people lose confidence in the way they speak. However, most people are 100% intelligible once the facial muscles are no longer droopy. One way of gaining some objectivity of how you sound is to record yourself. Read from a passage or recite a poem and then listen back. You will probably be surprised at how good you sound and that you can understand everything very easily. It is often just a matter of confidence and most likely that your speech feels different rather than sounds different. Feeling that your speech is different may link to muscles being tight and some muscles inhibiting others from moving freely. Carry on with all your rehabilitation and perhaps focusing on key muscle releases for the buccinator and orbicularis oris.

Read more

Photo by Volodymyr Hryshchenko on Unsplash